Lucretia was finally on a board. She couldn’t resist the impulse to get out to Los Angeles. The topics to be covered in the conference included all things related to women, gender, and the importance of the novella. She was planning to write more on these topics and had been invited by a friend, another female writer, who also had published novellas from small presses. Both Lucretia and her friend had well-established husbands who had published volumes and epic novels with big name publishers. Both women lived in New York, but Lucretia and her husband were the only couple to remain in Manhattan. They had no children, a bit of a sore point between them, a point that had come up before at one of her rare readings: what did she know about children? She did explain to them that she was a fiction writer and therefore capable of research and imagination. She said she had also been a child once, if that made any difference. It never escaped her to feel bemused that her husband, the well-known novelist, had written extensively about children in his books. But no one ever questioned him.

Lucretia and her husband had a two-story walk up on MacDougal St. across the street from Patti Smith, whom they knew on a first name basis. Many of their acquaintances, including Patti, didn’t know that in addition to her husband, Lucretia was a writer. The subject of her also being a writer had come up at one of their dinner parties. Lucretia had again published a novella with a small press and her husband was openly commending her talent. “My wife the talent!” were the words he chose to express himself. This of course prompted a larger conversation, many asking Lucretia what it was exactly she had done. She had written another small novel, she told them. Since her editor, whom she felt entirely grateful to have, suggested she stay brief in her ambition, she kept this detail to herself. Her latest novella entitled, Panel vs. Board, was about two boxers that always tied. It wasn’t satire exactly, it wasn’t metaphor either, she explained. “It’s just a small story,” she said to those asking. Her husband beamed, as he always did, when she’d open up a little about herself.

Lucretia had received many invitations to attend panels and to join boards, all of which, until very recently, she had coolly declined. She couldn’t commit to two words that in nearly every respect were the same. They both could mean a separate or distinct part of a surface, something she felt she could connect to, since she too felt like a part of a surface.

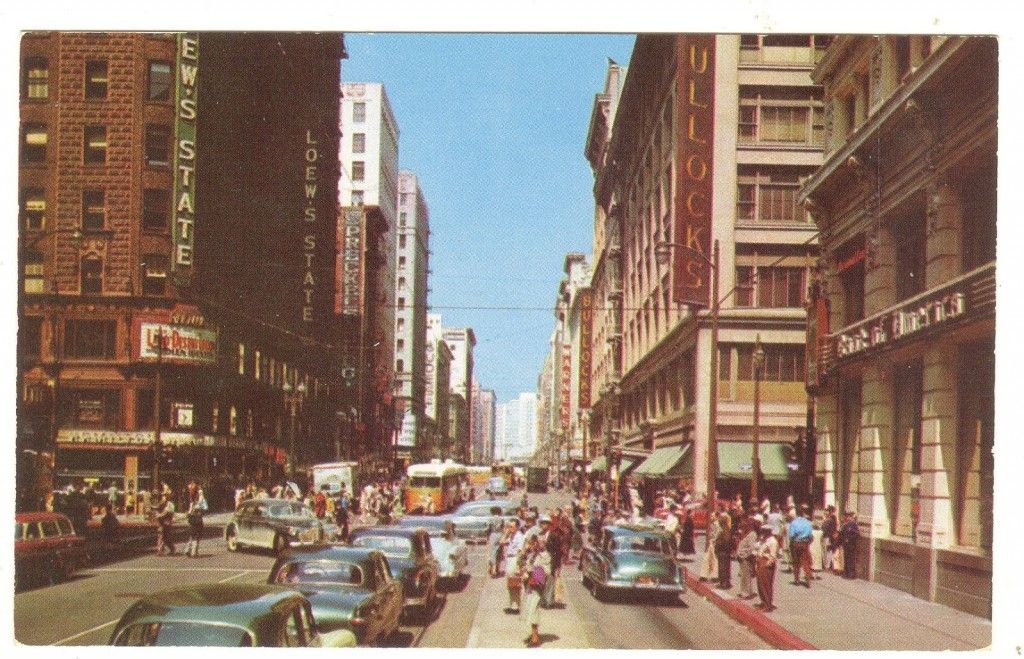

When she arrived in Los Angeles the weather was not what had been advertised on the plane. It was sunny and bright, and she noticed this was reassuring to all those visitors coming in from out of town. It was sunny, and the reports the pilot reiterated had suggested slight drizzle. Although, no one during the radio broadcast she was listening to driving into downtown from the airport felt the need to commit to any particular, “chance of rain, maybe complete sun.” It made some sense, she reasoned, given the size of Los Angeles with inland areas, mountains, valleys, and coastal regions. How could one know for certain?

The young man working the mini store in the lobby of the downtown hotel where the conference was being held ran out of sunglasses in less than an hour.

“After all you’re in Los Angeles” he explained to her, “and it’s hard to avoid the desire to feel discreet in Los Angeles.”

“I thought the desire was to avoid wrinkles forming around the eyes."

He offered Lucretia his extra pair, pulling the shades from an army bag, saying they belonged to his predecessor who had left the job and returned to Colorado where he claimed the air was fresher.

“And thinner and dryer,” she added.

The young man had never been out of Southern California, and as he said, he couldn’t see any reason to. The young man explained to Lucretia that if she wasn’t fond of the extra pair she could surely locate some in the ‘lost and found’ department. She took the neon plastic sunglasses and thanked the young man.

Outside the sun was blasting, the heat more than she could bare. It wasn’t as though summers in New York weren’t swelteringly painful, it was more that in Los Angeles the expectation was to be better than, or distinct from, your previous self. All this to say that in a place like Los Angeles Lucretia felt she needed to look well-maintained at all times, like Joan Didion had looked all those years she'd lived there.

Young girls with sun-bleached locks skated by on roller blades.

“They’re tourists,” the young man from the mini store pointed out as he lit a cigarette. He told her that people don’t roller blade downtown and that people moving to Los Angeles from the Midwest, or Colorado, generally looked more Californian than Californians.

“What about people from New York?”

“Oh, those people don’t visit at all, and if they do, they bitch and moan the whole time,” he answered.

She asked the young man for a cigarette and offered him a five-dollar bill since she felt rude taking again something for free from someone as young as he was. She had her own pack but that wasn't the point. He refused the bill and Lucretia lit up.

The taste of tobacco made her horny, she thought about her days in graduate school. She would sit at her desk that looked out onto a hospital parking lot and write. Her husband, then her skinny boyfriend, would snuggle up to her, kissing her ears, wrapping his tongue around her lobe. He’d do this to her lobes and she’d picture small pigs in a blanket and think about how as a child she was forbidden to eat such things. Her then boyfriend would traipse about their small apartment in Providence, R.I., naked and consistently erect. He told her that watching her work was too arousing, “I can’t concentrate, and how about a break to nibble?” Lucretia thought about when they married it was she, and not he, who was expected to be the more successful one. She wasn’t sure what had happened despite the piles of self-help books her mother insisted she read. She read a few but in the end they were all the same: she was burdening herself and she should work hard to unburden herself. It was not as though Lucretia was unhappy, she had just found herself in a place so familiar, a place she had read about numerous times before, that it made her ill. As a result she dismantled her smart phone and took up smoking. She refused to offer an explanation to her bewildered husband who now was pounds heavier and roamed about their home in a robe. She no longer wanted to debate the subtle suggestion of font types or whether prosecco was worth the cost or whether or not one should just hold out for champagne. In fact, she wanted to say out loud that she loved Italy more than France, but she knew it would create a social mess. It wasn’t that Lucretia felt she was being detained from her own life, or the things she aimed to create, she just felt that the epic novel had been defined and she had not been included in its definition. There wasn’t any room for her in the way there was room for great writers such as her husband. She felt catty and went in her bag for a cigarette. Essays, personal and otherwise, novellas, and short stories, these were the forms most available to her, and there was nothing inherently wrong with that. She could even dabble in song and poetry, if she felt obliged. She did feel lucky.

Lucretia lit a cigarette only to put it out immediately. She knew she could do something about it, join a women’s club or Facebook page, but she wasn’t compelled to participate in that discourse, it made her uneasy. She wasn’t one to complain, and when she’d say that to her mother, her mother would retort, “it’s not complaining, Lucretia, it’s getting what you want.” She continued her novella writing. She had come to understand one advantageous aspect of small presses: they didn’t mind her nonlinear, untraditional approach to writing. And despite the fact that she didn’t like being pigeonholed as “non-linear” and “untraditional,” she increasingly didn’t mind going unnoticed. When she viewed her husband’s career, she saw a gregarious monster of an ego, she saw a man who wrote to be noticed. Others viewed her husband’s career as forthright and lovable. Both men and women found him wildly charming but safely docile. Women felt he understood their inner selves, and men congratulated him. His readers were grateful he could produce sympathetic male characters while keeping female readers satisfied. Her husband was known notoriously for being easygoing and undyingly, even emotionally, erudite. He was engaging even to those who didn’t read; he didn’t step on anyone’s toes. Lucretia admired his undoubted commitment to himself. She should want to say things about herself, open herself up to the world, and let the world inside. At the very least open herself up to their immediate community, her husband had requested many times. Her agent had advised her it would be helpful to her career. Her agent, along with her mother, had suggested Lucretia make use of her commanding presence and attractive gait. She lit another cigarette and smoked it down to the butt, inhaling the last drag deeply. She forgot about exhaling and in her flurry she no longer found the Los Angeles heat oppressive.

Lucretia woke up at five p.m., her mouth tasting of tobacco and whiskey. The young man from the mini mart in the lobby was in bed next to her. His cotton v-neck still on his fit but small body. She had taken him back to her room, had given him head and then they had fallen asleep. The hotel phone rang and the young man jolted awake.

“The flight was easy, up and then down,” she said into the receiver. And, "Don't forget the plants in the spare room."

The young man was now up, putting on his trousers, lighting a cigarette. Lucretia waved to him to open the doors that led out onto a large patio overlooking a marble blue pool. She stood up unabashedly, her thin but toned body there in the barely dimming natural light to be seen. He looked in at her from the balcony, the gape in his mouth large enough to lose his cigarette. He removed it before it had the chance to fall out and made it obvious he was ready for her. She said goodbye and hung up the phone.

The conference began at seven a.m. Lucretia had met the friend who’d invited her at the café in the lobby. They had coffee and refrained from embracing the displayed buffet items. They would soon be entering a conference room the size of the Titanic brimming with muffins, cakes, Danishes, etc. Her friend asked how she’d slept and commented on how well Lucretia looked after a long day of travel. They talked about the weather back home in New York and the topics included in the conference. She asked Lucretia if she would be willing to discuss what it was like to be married to a famous author because they, the others organizing the event, had thought it would be of interest to the majority of guests.

“You know,” she said, “people just want to know what it’s like to be married to someone so talented.”

Lucretia nodded diagonally, and bit at her thumbnail. She could still smell the young man. “You know, Lucretia, people are very interested in the fact that you’re both writers, married, living in New York City and childless. It’s a rare breed these days since children are as popular to bear as buying organic,” her friend went on.

Lucretia scolded herself for accepting the invitation. She'd been wary that this conference, like the others, would want her to discuss her husband’s first novel. It was his breakthrough. It sold more copies than The Catcher in the Rye had and had ricocheted him into the highest of literary stratospheres. It was an epic novel about Lucretia and about their life together. He had not told her that all of the things she’d confided in him would one day make the page. He had not told her he’d borrowed her words both written and oral in order to cast a clear and honest picture, “a raw and very human ambiguity” that would become the hallmark of his work. He had not told her she wouldn’t be credited as co-author because, as he explained, "writers don’t really do that sort of thing.” She had never spoken publicly about the book, not even when he implored her to, or to at the very least speak to its gravitas at the book launch. Here she was in Los Angeles caught like a fish on a line.

“Yes,” she said under her breath, “caught in something as generic of a phrase as that one.” Realizing she had uttered the sentiment aloud, she lit the cigarette that had been stored behind her ear, something she'd noticed the young man do.

“Lucretia, this café is non-smoking. In fact you can’t smoke inside anywhere, it’s the same as in New York,” her friend told her.

“Guess I better take it outside then,” Lucretia said, as she stood up.

Lucretia sat down with the other panelists at five to seven. They had reiterated over the loud speaker how essential it was to begin the process on time. The trays passed from panelist to panelist were overflowing with pastries and bite-sized sandwiches. “Would you like a slider?” another panelist offered. She nodded and stuffed a few bite-sized sandwiches in her bag to give the young man who appeared to her to be underfed. She had watched his ribs all night as he breathed, with each breath nothing inflated. He had nothing to lose but one goldfish, nothing to care for other than the small fish he called Hard Wired. Lucretia had a fish once, a guppy in a bowl that lived in their kitchen. They'd only had it a short while before it jumped out onto the counter. It took her a few days to notice, her husband had been away at a conference in Europe. She put the dead guppy in the freezer hoping to one day give it a proper burial.

The conference began. It was rough at first since they couldn’t get the overhead projector to work and the hotel receptionist kept running back and forth in her tight skirt and wobbly heels until she finally burst out into tears, “This is not my job!” At least one person in the audience applauded her, or so Lucretia thought before the images of transgendered, multi-racial female couples with their families showed up on the screen wedged between the pages of a thin book. The title: The Novella: Women, Gender, and the Page. Each panelist introduced those to the left of them. Lucretia had not been prepared but managed to get something out of her mouth that resembled an informative compliment. After introductions they rattled through matters from the role of childbirth as fodder for female writers, Lucretia kept her mouth locked shut, to elementary principles of writing, notably concision, she kept her comments brief. The panelists failed to discuss the novella, and she didn’t remind them.

What was it that made breasts so uncomfortable not only for the woman who has them but also for the men who look at them? Lucretia thought when the panelist next to her finished explaining the plight of the good American novel. If she exposed a breast right then and there, it would make everyone in the room uncomfortable, despite the fact they’d all at one point in their existence had one in their mouths. As another panelist wrapped up her comments noting the group had digressed and in doing so had failed to address the importance of the novella, she had in fact said “impotence” and this set the crowd alight with laughter.

“Regarding the evolution of the novella, let me just say novellas are no less a novel than their fellow counterparts,” the panelist said, closing out.

Lucretia thought about how the baby kitten she’d rescued had turned out to be pregnant at the same time the Dominique Strauss-Kahn saga began, the saga that included a hotel maid. In 2011 Will and Kate married, and Senator Gabrielle Giffords was shot in the head. It was the same year Osama Bin Laden was killed. It was a big year, it was the year her husband won another prestigious award, and in the crowded and decorated room he had in his acceptance speech, dedicated it to her.

“This one’s for Lucretia Williams,” a young woman said with big black sunglasses on. It was bright in the conference room. There were many skylights and windows so Lucretia didn’t think twice about it. But she did wonder where her shades had gone. Had she misplaced them?

The young woman went on, “You’ve been married to Mr. Williams for many years. You met in college and he followed you to graduate school. Yet, you rarely speak about his work even though you too are a writer. You speak even less about your personal lives even though all of his work seems devoted to it. Can you explain why now you are here open to answering these questions? I do recognize mine is the first and perhaps the last…” this final part was muddled. Embarrassed, the young woman struggled to comfortably sit back down. The room went quiet. Lucretia fumbled around in her coat jacket for a lighter and began telling her, and all those present in the conference room, about her latest novella, the one about the two boxers that never won. Two boxers, one named Panel and one named Board, that always tied no matter how many bouts they fought. When she was asked to expand further, to get back to the question at hand, “what about Mr. Williams?” she took out a cigarette and said, “I am pretty sure I am not forgetting anything.”