There was, truly, the Polish language plastered everywhere. The television had Polish subtitles. The beer list was in Polish, Bud Light transcribed into Bud Light, but in Polish. The man behind the counter introduced himself as he walked in and said: You are here for your workers, no?

She said, Nice meeting you, André, are they the ones in the booth over there, by the wall?

—No silly shy girl they are here, at the bar with me, come now, calm down, take jacket off, take everything off and sit sit. Sit.

It had been true. They were stool sitting, relaxed, at the bar. Each one of them. Not that she knew “each one of them” but recognized their faces, vaguely their names. In order:

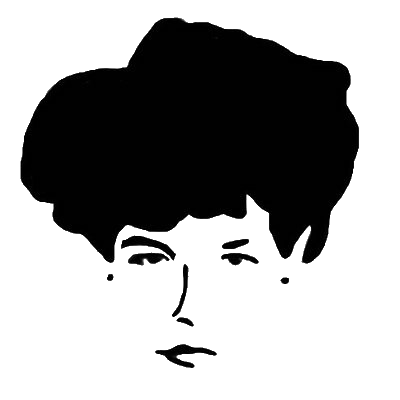

Gillian Daryl Tom Sharon (Shanon?) Clark Jack (or was it Jackie, she was never sure) Lauren B. Laurie B. Stacy Linda was not present. Linda was her boss. Linda was this in the mornings: She walks in, her pixie-cut black hair, eyeballs so large the whites barely frame pupils. Her head, huge head, resting on her neck like a queen, rising over a dress collar, rising over the rest of the heads in the room.

Linda was not there. Not present. Too busy? She tapped Gillian on the shoulder.

But her eyeballs, Linda’s, Emily thought of: of course, she’s busy, at home, busy, with her—did she have a husband, Emily had never bothered to ask—or was afraid to ask, of the answer, but— no, impossible, she must have had a boy—friend, the thought made her—she turned to Gillian, opened her mouth, parted those lipsticked flappers and before she could utter even a Hiya!:

—Get me the god fuck out of here. Gillian, Emily knew from the brief friendship she feigned with this particularly red-headed co-worker, was draining the company of its paper resources to write a play she called: Harry and Honey Go to the Theater, some self-referential satire about Theater and Plays which, as Gillian had told her in the lunch room, was about people paying for make-believe, as if they couldn’t act the part in front of their friends for free in the living rooms of their apartments.